Why I Chose Jin Yong's Fiction for This Blog: Female Figures in Martial Arts Stories

Female Figures in Martial Arts Stories

When I began this blog, I wasn’t only trying to understand fictional women —

I was trying to understand myself.

A woman shaped by Chinese values, now living in a modern world that doesn't quite match the rhythm I was taught to move in.

Jin Yong’s wuxia fiction became my mirror.

Jin Yong (Louis Cha) was not just a storyteller. He was a man writing in a time of massive transition —

a voice emerging from post-World War II Hong Kong,

a city caught between collapse and reinvention.

After 1949, Hong Kong became a refuge for mainland Chinese escaping revolution, trauma, and political purging.

It became a British colony still holding onto Chinese values, and a rising capitalist port,

where survival meant adapting — quickly, often silently.

Families were reshaped. Tradition collided with new money.

And women, especially, were trapped in contradictions.

Men’s Expectations Were Torn in Three Directions

In Jin Yong’s time, men didn’t know what they wanted — but they knew what they feared:

The Confucian good wife: quiet, composed, obedient.

The resourceful refugee woman: tough, capable, frugal, emotionally reserved.

The modernized ideal: educated, well-dressed, Western-influenced — but still willing to submit at home.

💬 “She’s strong, but still knows her place.”

💬 “She’s smart, but doesn’t challenge me.”

💬 “She works hard, but won’t make trouble.”

This is the world Jin Yong was writing into — and against.

Why His Women Matter

Many readers admire Jin Yong for his plots, philosophies, or swordplay.

I read him for the women.

Not because they are feminist icons in the modern sense — but because they are quietly subversive.

They survive, love, lead, suffer, and sometimes win — without ever becoming loud.

✦ Ren Yingying

A cult leader who never shouts

A strategist who never begs

A lover who never loses herself

She is calm, perceptive, and always emotionally composed — not because she lacks feeling,

but because she guards it with dignity.

✦ Huang Rong

Clever, fast-talking, disobedient — but only to those who don’t deserve her

Loyal, fiercely intelligent, and often misunderstood — even by the man she loves

These characters carry what I would now call autistic-coded traits:

emotional internalization, moral clarity, sensory precision, quiet loyalty, social selectivity.

Traits that, in today’s language, might be pathologized — but in Jin Yong’s world, help them survive.

What This Blog Really Explores

This isn’t a project about autism in a clinical sense.

It’s about how emotional restraint, introverted perception, and relational discipline — especially in women —

can be re-read not as signs of deficiency, but as wisdom.

Women like Ren Yingying or Huang Rong wouldn’t thrive in today’s hyperverbal, emotionally performative world.

But in Hong Kong’s postwar complexity — where women had to read contradictions and manage contradictions —

they didn’t disappear.

They stayed.

They observed.

They endured.

And for women like me —

who feel too slow for modern capitalism,

too precise for small talk,

too loyal for casual love —

these characters offer something precious:

A reminder that quiet does not mean weak.

That internalisation is not failure.

And that surviving with your values intact is a kind of martial art too.

Ren Yingying: The Still One Who Holds the Blade

A woman who leads without shouting, loves without losing herself, and survives where louder women vanish.

In a world of power struggles, cult politics, and secret martial codes, Ren Yingying moves like water — soft, quiet, but never weak. She does not chase the spotlight. She does not cry to be understood. And yet, when she steps forward, others make room.

She is not the heroine who fights for attention.

She is the one who notices everything before anyone speaks.

She reads the room, reads the people, and holds her feelings like a blade behind her back — hidden, but sharp.

Most readers remember her as the Sacred Maiden of the Sun Moon Cult, a woman caught between violence and loyalty, love and leadership. But I remember her as something else:

A woman who never gives herself away too quickly.

A woman who feels deeply, but doesn’t perform it for others.

A woman whose strength is not in dominance — but in discernment.

She is a model of emotional self-regulation, not because she is cold, but because she knows what it costs to be vulnerable in front of people who haven’t earned her trust.

What She Teaches Us

To many modern readers, Ren Yingying may seem distant. She doesn’t rant. She doesn’t fight for validation. She doesn’t even say much about her love — she simply stays.

But to those of us who have felt misunderstood, who prefer silence to chaos, who survive by choosing when and how to show ourselves — she is a quiet mirror.

She reflects what it means to:

- Love with boundaries

- Lead without ego

- Sense what others miss

- Hold onto your identity in a relationship

- Choose stillness, not submission

Neurodivergent Traits in Her Character

| Trait |

Behavior in Ren Yingying |

Reframed Meaning |

| Social selectivity |

She connects deeply with few, especially Linghu Chong |

Loyalty as discernment, not lack of empathy |

| Emotional regulation |

Rarely shows emotional outbursts |

Strength through internal balance |

| Strategic silence |

Often observes rather than speaks |

High situational awareness |

| Moral clarity |

Acts based on principle, not impulse |

Self-trust without external approval |

| Devotion without performance |

Loves Linghu Chong without drama or demand |

Secure attachment; quiet relational power |

Why She Belongs in This Blog

Ren Yingying is the kind of woman who might never speak up in therapy.

She might not be “neurodivergent” by Western standards.

But she reminds us of the emotional cost of constant self-exposure — and shows a path of survival through intelligent withholding, careful loyalty, and quiet love.

She is not here to explain herself.

But she stays until the end of the story —

whole, steady, and still herself.

Classic scenes

Green Bamboo Lane: The Listener Behind the Curtain

Scene (recast): Linghu Chong, disgraced and weary, finds refuge in a quiet courtyard. A woman’s voice behind a bamboo curtain invites him to share his burdens. She doesn’t advise or correct—she simply listens, as though holding space for his pain. Then, through the strings of a qin, she weaves calm back into his soul.

The quiet companion—someone who doesn’t fix, but understands. It echoes the longing for emotional intimacy without pressure, a sanctuary where dignity returns.

Wubao Ridge: The Woman Behind the Chaos

Scene (recast): A rowdy inn is suddenly filled with misfits and rogues who shower Linghu Chong with aid. Slowly it’s revealed: this storm of loyalty is not random—it’s her doing. She, the unseen woman, commands respect from the very margins of society.

The hidden matriarchal strength—not ostentatious, but quietly commanding. It recalls the female ability to organize loyalty and protect loved ones, even in unruly settings.

The Siege of Shaolin: Love as a Choice

Scene (recast): Yingying bargains her own freedom so that Linghu Chong may live. She does not weep or play the martyr; instead, she calmly places her hand upon his, saying, “This is my decision.”

The dignified sacrifice—choosing to bear a burden for love without fuss or drama. It echoes British ideals of love as commitment, often shown through quiet endurance rather than grand declarations.

Black Cliff: When Love Turns Practical

Scene (recast): In the chaos of battle, Yingying makes the hard decision others cannot: she strikes at the foe’s hidden weakness. She bears the moral cost herself, allowing others to keep their honor.

The pragmatic partner—doing the necessary, even if it feels ruthless, because survival and loved ones matter more than appearances. This mirrors a British appreciation for quiet realism in hard times.

Mount Heng: The Woman Revealed

Scene (recast): The mystery unravels—she is at once the voice of comfort, the leader of outlaws, the strategist. Yet when Linghu Chong embraces her, all masks fall. She blushes, awkward, suddenly just a woman loved.

The mask-and-heart tension—the ability to be both capable and tender. Many women will recognize the longing to be seen not just in their competence, but in their unguarded softness.

The Final Choice: Freedom Over Power

Scene (recast): Offered dominion over a vast empire, she simply says, “No. I’d rather sing with you in the hills.” The world calls it folly; she calls it freedom.

The turn from status to simplicity—rejecting hollow victories in favor of authentic companionship. This echoes the British value of a life well-lived quietly, garden over empire, music over power.

Huang Rong: The Clever One Who Tests Your Heart

A girl who jokes before she trusts, outsmarts before she loves, and stays only when she’s truly seen.

Huang Rong appears as a whirlwind — clever, mischievous, dressed like a beggar but speaking like a princess.

She plays with people’s expectations.

She hides her depth behind laughter, her pain behind tricks.

To most, she is dazzling. To some, exhausting.

To those who watch more closely — she is precise, loyal, and braver than she appears.

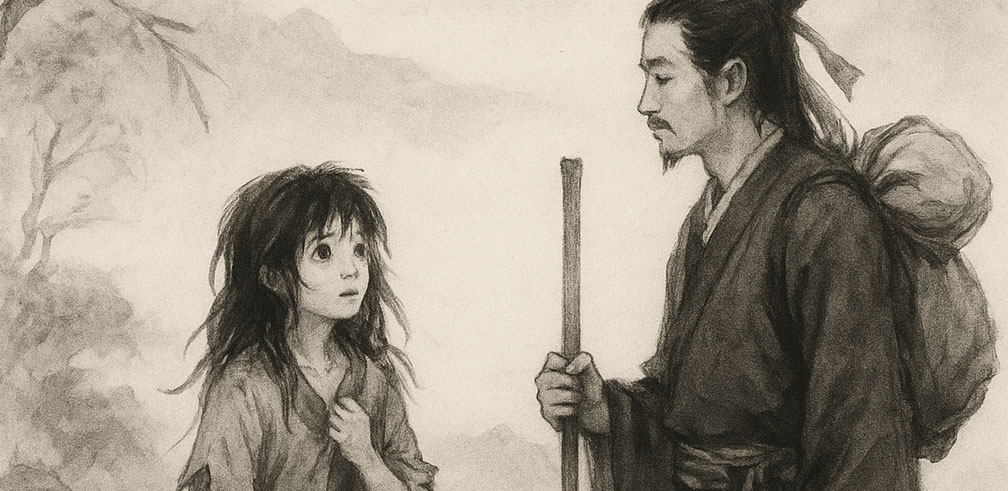

When she first meets Guo Jing, she teases, tests, and outwits him.

But it is not cruelty — it is caution.

Her mind is fast, but her heart is slow.

She knows what it means to be underestimated, misread, envied, or used.

So she learns to mask. She learns to manipulate.

And eventually, she learns to love — but only in her own way.

Huang Rong is not a gentle woman. She is a survivalist.

She makes herself useful because she knows it keeps her safe.

She loves Guo Jing not because he is clever (he is not), but because he is steady, kind, and never asks her to become someone simpler.

What She Teaches Us

In a world where clever women are often punished or flattened, Huang Rong survives by being both:

- A strategist who solves problems no one else can

- A daughter who carries the loneliness of being “too much”

- A lover who holds deep affection inside layers of performance

She shows us that intelligence, when combined with emotional sensitivity, becomes a way to create safety — not just for herself, but for those she trusts.

She teaches that:

- Not all teasing is cruelty

- Not all chaos is confusion

- Not all silence means disconnection — sometimes, it means calculation or care

Neurodivergent Traits in Her Character

| Trait |

Behavior in Huang Rong |

Reframed Meaning |

| Verbal masking |

Uses humor, sarcasm, storytelling |

Protects vulnerability through play |

| Deep loyalty |

Devoted to Guo Jing despite mismatch in intellect |

Bonds based on moral trust, not status |

| Emotional selectivity |

Slow to open up; tests others before trusting |

Relational discernment, not manipulation |

| High systemizing |

Strategizes meals, battles, social manipulation |

Uses logic to navigate chaos |

| Sensory sharpness |

Reacts strongly to taste, music, tone |

Embodied intelligence; heightened sensitivity |

Why She Belongs in This Blog

Huang Rong represents another kind of neurodivergent woman:

The one who hides herself in noise.

The one who jokes too much because being sincere feels unsafe.

The one who uses her mind to stay ahead — because her heart has been misunderstood too many times.

She may not be emotionally composed like Ren Yingying.

But her internal struggle is no less disciplined.

And her survival is not by chance — it is the result of constant calibration between performance, intelligence, and hidden loyalty.

She is not always easy to understand.

But she never forgets the ones who pass her test.

She stays with the one who gives her room to be clever —

and never once asks her to become quiet.

Classic scenes

The Island Encounter: A Girl in Rags and Bright Eyes

Guo Jing first meets Huang Rong disguised as a ragged beggar girl, yet her sharp eyes and quick tongue shine through the dust. She tricks, teases, and tests him, revealing her playful intelligence long before her beauty or lineage are known.

This is not love at first sight through appearance, but through character. British women readers may see in her the joy of being valued for cleverness and wit, not just surface charm.

The Peach Blossom Island: Daughter of the East Heretic

When Guo Jing discovers that the mischievous girl is in fact the daughter of the eccentric master Huang Yaoshi, it reframes her entirely. She is heir to brilliance and rebellion, caught between filial duty and her own independence.

Many women understand the tension between family expectation and personal freedom. Huang Rong embodies the struggle to honor roots while shaping her own path.

The Beggar Sect Challenge: Cleverness as a Weapon

During the Beggar Sect turmoil, Huang Rong uses her cunning strategies to outwit opponents far stronger than herself. While others rely on brute force, she wields wit as blade, guiding Guo Jing and reshaping the tides of conflict.

The dignified sacrifice—choosing to bear a burden for love without fuss or drama. It echoes British ideals of love as commitment, often shown through quiet endurance rather than grand declarations.

Loyalty in Danger: Sharing Poverty and Risk

When Guo Jing is framed, hunted, or at his lowest, Huang Rong never abandons him. She chooses exile, hunger, and danger by his side rather than safety apart. Her loyalty is not blind — she scolds him fiercely — but it is steadfast.

Why it matters: Her love is both playful and unwavering. Many readers recognize the depth of affection that can argue, tease, and yet endure through hardship.

Xiangyang: Wisdom of the Matriarch

Later in life, Huang Rong matures into the Lady of Xiangyang, mother of Guo Fu and Guo Xiang, and strategist defending the city against Mongol forces. She balances tenderness with tactical genius, still sharp-witted yet carrying the gravity of responsibility.

Huang Rong’s arc is rare: she grows from trickster girl into wise matriarch without losing her spark. She offers a vision of womanhood that is playful, loyal, and enduringly strong across all ages of life.

Huang Rong: After the Romance Ends

GMost heroines in love stories vanish after the wedding. Their charm is captured in the glow of youth, their role fulfilled once the hero takes their hand. But Huang Rong is different. In Jin Yong’s The Legend of the Condor Heroes, her story does not stop at romance. It deepens.

When she first appears, she is a playful trickster in beggar’s rags, dazzling Guo Jing with wit sharper than any sword. Their courtship sparkles with teasing and tests. This is the “romantic climax” many tales would end on. Yet for Huang Rong, marriage is not an ending—it is a threshold.

Together with Guo Jing, she defends the city of Xiangyang against Mongol invasions. She becomes strategist as well as wife, her quick mind guiding armies while her husband’s courage holds the gates. Where he is honest and steady, she is cunning and inventive. Their bond is not frozen in youthful passion; it is tempered into partnership.

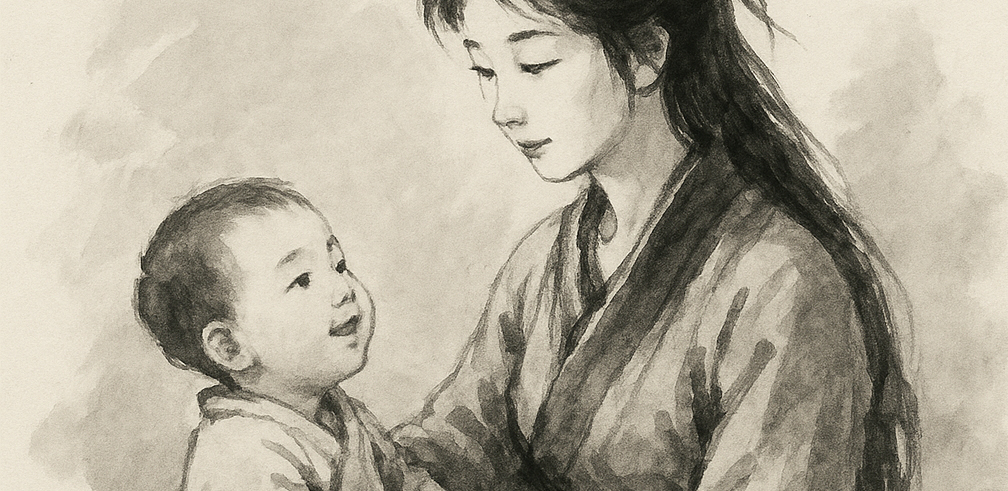

And then, motherhood. Raising daughters reveals new sides of her: tenderness, bias, even sternness. She indulges Guo Fu, whose wilfulness brings trouble, but she also nurtures the spark in Guo Xiang, who grows into an independent spirit. In these contradictions—loving, protective, sometimes flawed—Huang Rong becomes profoundly human.

Her character changes, but her essence remains. The sharpness of mind that once tricked opponents now plans defenses for a city. The mischief of a beggar girl matures into the wisdom of a matriarch. She grows older, but never smaller.

For British women, her story resonates because it refuses the illusion that life is only about falling in love. Huang Rong shows what comes after: the long work of building a life with another person, of raising children who do not always reflect us, of balancing loyalty and responsibility with the stubborn wish to remain ourselves.

In her, we see the arc that so many women live but so few stories honor: the girl who becomes wife, partner, mother, and leader without losing the spark that first made her unforgettable.

Huang Rong teaches that romance is not the end of the tale—it is only the beginning of a woman’s truest story.

Her Wit

“Wit sharper than any sword.”

From beggar’s rags to strategist’s desk, Huang Rong proves that cleverness can protect as much as strength.

Her Partnership

“Side by side at Xiangyang.”

Guo Jing’s courage and Huang Rong’s cunning make them equals in love and in war, a model of enduring partnership.

Her Motherhood

“Tender, biased, protective.”

Her daughters inherit both her flaws and her brilliance, showing the complexity of love passed to the next generation.

Her Maturity

“Older, but never smaller.”

She grows into a matriarch who still sparkles with mischief, proving that a woman’s essence need not fade with time.

Yin–Yang Balance vs. Western Feminism

How different frameworks imagine strength, partnership, and a heroine’s life after marriage — with Huang Rong as the living bridge.

| Theme |

Yin–Yang Lens |

Western Feminism |

Huang Rong as Example |

| Core Idea |

Harmony through balance of opposites |

Equality through resistance and rights |

Balances Guo Jing’s honesty with her cunning, creating partnership |

| Strength Defined As |

Both soft (yin) and hard (yang) powers are vital |

Often measured by access to traditionally male domains (career, power, voice) |

Uses wit and strategy as power equal to Guo Jing’s martial strength |

| Approach to Conflict |

Seek complementarity; adjust roles for balance |

Challenge and resist structures of patriarchy |

Does not rival Guo Jing; balances his bluntness with subtlety |

| View of Partnership |

Mutual dependence; yin shapes yang, yang shapes yin |

Independent equality; caution about subordination |

Works with Guo Jing, not beneath him, not above him |

| Life After Marriage |

Ongoing evolution of balance — roles shift, both endure |

Historically less emphasized (focus on breaking barriers) |

From trickster girl → strategist wife → mother → matriarch |

| Ideal Outcome |

Wholeness, harmony, resilience |

Freedom, independence, equality |

A partnership that defends Xiangyang and raises the next generation |